2021 Panel Discussion: Martial Law in Poland 1981-1983 (REPORT)

Panelists speaking in the Veterans Room of Polish Center of Wisconsin (from left to right): Irena Frączek (PAC, PHC, event organizer), Andrew Woźniewicz (PAC), Julita Zolnik (PHC), Ryszard Zolnik (PHC), Jacek Franczak, and Szymon Woźniczka (PHC). All panelists were born and residing in Poland at the time. Places they mentioned are marked on the map below.

Photo: Karen Wieckowski.

……………

WE REMEMBER

Panel Discussion

Martial Law in Poland 1981-1983

Irena Frączek reports……

On December 13, 2021, the Polish American Congress – Wisconsin Division (PAC) and Polish Heritage Club Wisconsin-Madison (PHC) co-sponsored a memorable panel discussion held in remembrance of the 40th anniversary of martial law imposed in Poland on December 13, 1981. Prof. Donald Pienkos moderated the event, while Prof. Neal Pease delivered closing remarks. The event was hosted in the beautiful Polish Center of Wisconsin in Franklin.

Speaking first, Irena Frączek began by bringing up the specter of a Russian invasion weighting heavily on the peoples’ minds in 1981. She lived close to the Warsaw’s Okęcie airport and on some occasions, the noise of planes landing and taking off all nights long kept her fearful of what the morning news would bring. She was awake at midnight on December 13, 1981, when her radio went silent. Little did she know that at that time, the police and military was seizing all TV and radio stations, including the Polish TV headquarters, located just two blocks away on Woronicza Street. From there, General Jaruzelski’ speech announcing martial law was continually broadcast since 6 am. Half asleep, Irena heard it echoing through the neighborhood, but its actual content became clear only after an in-law came to talk over the implications of the shocking news.

The Wikimedia image above shows Polish T-55 tanks entering Zbąszyń, a small town near the Szczecin-Warsaw route (see the map below).

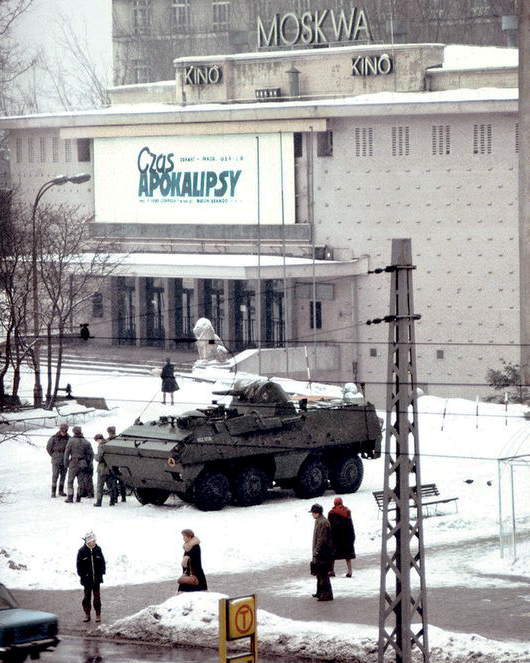

The symbolism of armored carrier parked in front of the movie theater called Moscow (Moskwa) playing Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” did not escape attention of Warsaw’s inhabitants. Preserved for posterity by the famed Chris Niedenthal, the shut – taken despite the ban on photographing – is one of the most iconic images of martial law. Source: DigitalCameraPolska

Not knowing about some arrests that hit close to home, the travel restriction and cut off phone lines became the main concern because her husband was expected to return from Western Europe on that Sunday. As it turned out later, he entered Poland just minutes before borders were sealed at midnight and defying the intercity traffic ban, he embarked on a harrowing backroads journey from Szczecin to Warsaw. Some tanks encountered on the road would push his car into the ditch, then sympathetic crews from other tanks would pull him out, also providing gasoline that by decree was unavailable to civilians. About three days later, he reached Warsaw only to learn with the rest of us about the massacre that killed 9 miners during the bloody pacification of the strike in coal-mine “Wujek.”

For Andrew Woźniewicz, martial law begun late at night on December 12th with an ominous sound of tanks rolling down the street. He looked through the window and what a relief: they were not marked with Soviet stars. Reactions of the world intercepted on the short-wave radio confirmed that this wasn’t a dreaded Russian intervention. With time, it became clear that the swift crackdown on 320 cadets striking in Warsaw’s Firefighters Academy just ten days earlier was a dry run for the planned martial law. Andrew witnessed the entire operation from a streetcar stuck in the stopped traffic. No blood was shed but the full-blown ZOMO (special units of riot police) assault, aided by the helicopter landing on the roof and the military cordoning the academy off, was the largest use of force since the birth of Solidarity in August 1980.

Another line in Andrew’s story was his own participation in strikes engulfing most of Polish universities in November 1981. As a freshmen med student, he joined a sit-in protest at the Medical University of Warsaw, where he met Fr. Jerzy Popiełuszko on multiple occasions. Fr. Jerzy became a major force in dismantling the communist regime thanks to his staunch opposition to the repressive communist system and extraordinary motivational powers. His unwavering espousal of peaceful resistance helped to shape the strategies of the Solidarity movement but failed to protect his own life. He was assassinated by Security Police (Służba Bezpieczeństwa, SB) on October 19, 1983.

The story of Jacek Franczak began at his

For his contribution to democratic opposition, Jacek Franczak was awarded the Cross of Freedom and Solidarity by President Andrzej Duda on Nov. 11, 2021.

The buses safely passed the cordons surrounding the plant and students joined thousands of strikers inside. One of the most important tasks of the AGH newcomers was assisting the production of printed materials and distributing critical information to the communication teams. Pacification of the strike began in the evening of December 16, 1981. Jacek avoided arrest on that night because two days earlier, he and his close friend were asked to “jump the fence” and collect some critical information and items on outside. He then helped to create a new underground organization ARS (Academical Self-Defense Movement). In short order, the ARS started printing a weekly newspaper “So Long as We Live” (Póki my żyjemy) providing Kraków’s students with information free of governmental control. He was involved also in printing and distributing “The Lesser Poland Chronicle” (Kronika Małopolska) published between 1982-1989 by the Solidarity forced underground.

In the meantime, Ryszard Zolnik was one of those highschoolers who enjoyed no school days at the first weeks of martial law. Yet soon, the loss of civil liberties, and particularly the freedom of movement, became unbearable. That’s why in June 1982, Ryszard showed up at the street demonstration organized in his hometown Dzierżoniów (Lower Silesia). Of course, all public gatherings were still illegal, and Ryszard got arrested along with many other participants. They were thrown into the trademark blue police vans called “

Like all his fellow arrestees, Ryszard was found guilty by special expedited court. The official penalty was a hefty fine that his parents had to pay before taking him home. But still in Nowa Ruda jail, they were all forced through the infamous “ścieżka zdrowia” (a painfully ironic use of the term “fitness trail”), i.e., the gauntlet of police beating the inmates with batons. The severity of beating was somewhat reduced for the younger “offenders,” but they saw the hard pummeling that knocked down an older prisoner. After returning to school, Ryszard was publicly reprimanded in front of the entire school for his “shameful behavior.”

For millions of ordinary Poles, humor became an outlet for venting anguish and resentment, as well as a form of non-violent retaliation against the oppressors. Jokes, epigrams, satires spread by the word of mouth, underground-printed materials or inscriptions on the walls. One of the best known puns was “The crow shall not defeat the eagle” (Orła wrona nie pokona), seen in the image above. The eagle epitomizes the Polish nation, while the crow (wrona in Polish) stands for the junta known by its acronym WRON (Wojskowa Rada Ocalenia Narodowego, i.e. the Military Council of National Salvation).

Image design: Jan Stańda. Source: Allegro website.

The Orła wrona nie pokona phrase weaves through the song recorded by the group DePress in Norway. Presented on the backdrop of martial law images, the song explains how the crow hatched out from a “red” egg and ends with another popular phrase “The crow will perish” (Wrona skona).

A spark of humor flashed in a story of Szymon Woźniczka from Zakopane. He was just 13 when martial law went into effect, but his understanding of the ongoing events was substantial. What helped was a family including avid readers of the underground publications and regular listeners to the Radio Free Europe and Voice of America. Another formative influence was Wojciech Niedziałek, a family friend with the past in Home Army (AK), and a history of being discriminated against and persecuted for his anticommunist views and activities. An additional inspiration for the incident shared on the panel came from the “memes” and jokes spreading like fire through the nation.

When schools re-opened in January 1982, Szymon and several friends expressed their disapproval of martial law and Solidarity dissolution by plastering school walls with handmade posters poking fun at the repressive junta and some of the most despised members of the communist party. Police was called in when one of the teachers recognized the handwriting styles. After landing in the police station, the boys were treated to a milder version of “

A few snippets of hardships in everyday life were interwoven in the story of Julita Zolnik from Warsaw. Also 13 at the time, she was old enough to remember empty stores and many other “unpleasantries” of the economic system on the verge of collapse. Martial law exacerbated these woes and increased the associated risks. For example, her father venturing to the countryside to replenish the dwindling food supplies risked jail time and/or fines for “illegal commerce” and/or ignoring bans on civilian traffic.

Other memories included tanks on the street, protests breaking up in the clouds of tear gas and ruthless beating of demonstrators chased off the streets by ZOMO. “They looked possessed” – said Julita describing a scene she witnessed in the courtyard of her apartment building. This observation aligns with rampant speculations that ZOMO thugs were being drugged before the action. Faced with those harsh realities, many young people chose to wear resistors (devices controlling current in electronic devices) on their clothes. They were tiny but big enough to efficiently conveyed the message: “We resist!” School officials noticed them too and soon, Julita and her classmates, one by one, were called to the principal’s office and subjected to threatening remarks that such “behavior” was sure to destroy their future by making them ineligible for admission to universities or ruining their parents’ careers.

The general discussion that followed these recollections began with acknowledging the essential role of church in those events. For individuals, even the non-religious ones, church provided places to gather, regain hope and get the otherwise unavailable information. For Solidarity and other independent organizations, church was the only option because the government controlled all other venues and channels of communication. Those organizations kept producing torrents of information that people could trust – in contrast to “fake news” peddled in the government-controlled media (known also as “mass disinformation”). In terms of numbers, Prof. Donald Pienkos recalled a report that one year, the regime confiscated around 600,000 copies of underground publications. But this was only a fraction of the huge, never intercepted totals and those served as a true lifeline for the oppressed nation because – as one panelist remarked – the need for truthful information is next only to the need for food keeping us alive.

From left to right: Professors Donald Pienkos and Neal Pease, both emeritus faculty of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

From left to right: Professors Donald Pienkos and Neal Pease, both emeritus faculty of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Photo: Karen Wieckowski.

The complicated issue of bringing the perpetrators to justice dominated the rest of discussion. In some cases, the main culprits remain unknown. For example, the three murderers of Fr. Popiełuszko and their immediate superior were tried and convicted, but who gave them the orders at the upper echelons of secret police has not been identified. Moreover, assessing culpability is often difficult – especially with on a personal level and with the passage of time. Finally, some perpetrators offered convincing justifications for their actions. The case in point was Gen. Jaruzelski himself, claiming to the end of his days that imposition of martial law was necessary to avoid the bloodshed and destruction inevitably coming with the widely feared intervention of Russian and/or the Warsaw Pact forces. The concept of “thick line” (gruba kreska) was also thrown into the mix. Articulated in the aftermath of the Round Table talks in 1989, the idea was to draw a line past which the sins of previous regime are forgiven, and instead, focus on extracting Poland from its plight. However, the resulting policy of de facto non-punishment became a source of emotional disagreements that continue until today.

In conclusion of this memorable evening, Prof. Neal Pease summarized martial law from the historian’s perspective. He briefly revisited the issue of whether Gen. Jaruzelski was a criminal or a patriot. The answer is unclear because judging by the opinion polls taken in Poland, the narrative of choosing the ”lesser evil” – whether Soviet invasion was likely or not – seems to resonate with general public. The historical context for further discussion was introduced with a paraphrased quip coined in the late 1980s: “In Czechoslovakia, the downfall of communism took 10 days, in East Germany – 10 weeks, in Hungary – 10 months, in Poland – 10 years.” Martial law was a part of those 10 years, and crackdown on Solidarity was its immediate target. But in fact, the crisis it aimed to redress predated those 10 years and the real issue was not Solidarity but the growing “incorrectitude” of the system. Resorting to the military rule appeared to be a desperate attempt to salvage the irremediable system and that’s why – despite exceptionally efficient planning and execution – it ultimately failed.

Last edits on February 1, 2022……

Archived Posts

- 80th Anniversary of the 1944 Warsaw Uprising

- 2024 Wianki Festival

- 2024 Polish Constitution Day in Wisconsin

- 2023 Merry Christmas

- 2023 Lighting the Light of Freedom on Dec 13 at 7:30pm

- Independence Day and Veteran Day invitation

- 2023 Wianki Festival

- 2023 May 3rd Constitution Day Celebration

- 2023 Lecture on Polish Borders by Prof. Don Pienkos

- 2023 REMEMBER THIS: Jan Karski movie premieres on PBS Wisconsin

- 2023 Upcoming lectures in the Polish Center of Wisconsin

- 2022 Polish National Independence Day

- 2022 Independence and Veteran Day Luncheon (invitation)

- 2022 Wianki, Polish Celebration of Noc Świętojańska (St. John’s Night)

- Celebrating Constitution of May 3, 1791 in Polish Center of Wisconsin

- 2022 Polish Constitution Day, Polish Flag Day and the Day of Polonia

- 2022 March Bulletin

- 2022 Polonia For Ukraine Donations

- 2022 Polish American Congress Condemns Russian Invasion of Ukraine

- 2022 PAC-WI State Division Letters to WI Senators and Representatives

- 2021 Polish Christmas Carols

- 2021 Panel Discussion: Martial Law in Poland 1981-1983 (REPORT)

- 2021 Panel Discussion: Martial Law. Poland 1981-1983 (invitation)

- 2021 Solidarity: Underground Publishing and Martial Law 1981-1983

- 2021 Polish Independence Day and Veterans Day

- 2021 Polish Independence Day and Veterans Day Luncheon

- 2021 Prof. Pienkos lecture: Polish Vote in US Presidential Elections

- 2021 POLISH HERITAGE MONTH EVENTS

- 2021 “Freedom” Monument Unveiled in Stevens Point, Wisconsin

- 2021 PCW Picnic and Fair

- 2021 Remembering Września Children Strikes (1901-1903)

- 2021 May 3 Constitution Day

- 2021 DYKP Contest Winners and Answers

- 2021 DYKP CONTEST EXTENDED and CASIMIR PULASKI DAY

- 2021 February announcements

- 2021 Polish Ministry of Education and Science oficials visit Wisconsin

- 2021 DYKP Contest, KF Gallery and Dr. Pease lectures

- 2020 Help Enact Resolution commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Katyn Massacre

- 2020 Independence And Veterans Day

- 2020 Remembering Paderewski

- 2020 POLISH HERITAGE MONTH

- 2020 Solidarity born 40 years ago

- 2020 Battle of Warsaw Centenary

- 2020 The Warsaw Rising Remembrance

- 2020 June/July News: Polish Elections, Polish Films Online and more

- 2020 Poland: Virtual Tours

- Centennial of John Paul II’s Birth

- 2020 Celebrating Polish Flag, Polonia and Constitution of May 3rd

- 2020 Polish Easter Traditions

- 2020 Census and Annual Election

- Flavor of Poland (Update 3)

- 2020 Copernicus, Banach & Enigma talk

- 2020 Do You Know Poland and other announcements

- 2020 Flavor of Poland (Update 2)

- 2020 People and Events of the Year

- 2019 Holidays

- 2019 December Medley

- 2019 Independence Celebration

- 2019 Independence Invitation