2021 Solidarity: Underground Publishing and Martial Law 1981-1983

REMEMBERING SOLIDARITY 1980-1981

Through the Lens of Independent Publishing

& Martial Law Imposed on December 13, 1981

August 31, 1980, marked the 40th anniversary of the birth of Polish Solidarity. On that day in 1980, the landmark August Agreement was signed between then the communist government of Poland and the Interfactory Strike Committee (Międzyzakładowy Komitet Strajkowy, MKS) formed on the third day of strike that erupted in Gdańsk shipyard on August 14, 1980. About 16,000 shipyard employees joined the protest but within a couple of weeks, around 1 million workers all over Poland went on strike as well. In this way, one of the biggest strikes ever ensued and the MKS became an alliance of numerous independent organizations. When signing the August Agreement on August 31, 1980, it represented about 3 million workers from nearly 3,500 enterprises. The rest of Poland was holding breath in hope that this rise will end in victory rather than a bloody finale like other strikes before.

For more about Solidarity movement, visit Professor D. Pienkos’ story

The Amazing Story of Solidarity Begins – 40 Years Ago

The firing of Anna Walentynowicz for her illegal trade union activity was a spark that ignited the 1980 strike in the Gdańsk shipyard but root causes run much deeper. Of course there were hikes of food prices and shortages of nearly everything – the ominous signs of economy on the verge of collapse. Living in Poland until 1983, I will never forget the dread of food rationing, the humiliation of standing in endless lines, or the misery of waiting 16-20 years for the already paid off apartment. Available in abundance, however, was the devious misinformation and stupefying propaganda spewed by the government controlled media. For me personally, a symbolic image of that reality was a neighborhood store with empty shelves and a few bottles of vinegar sitting on the counter next to a big pile of the state-run newspaper.

Striking workers wanted to participate in the process of taking the country out of the crisis and this desire was articulated as part o the famous list of 21 demands issued on August 17, 1980 and posted on the shipyard’s gate. After the government signed off on these demands on August 31, 2020, the nationwide labor union Solidarity (Solidarność) was registered on September 24, 1980. Amid the euphoria sweeping the country, Solidarity kept growing fast with students, intellectuals, farmers, and professionals joining its ranks. In September 1981, it had about 10 million members (in a country with a total population of 35.5 million). Moreover, surrounding its trade union core, Solidarity became a de facto social movement and one of its most important imprints was exerted in the area of what became available for people to read.

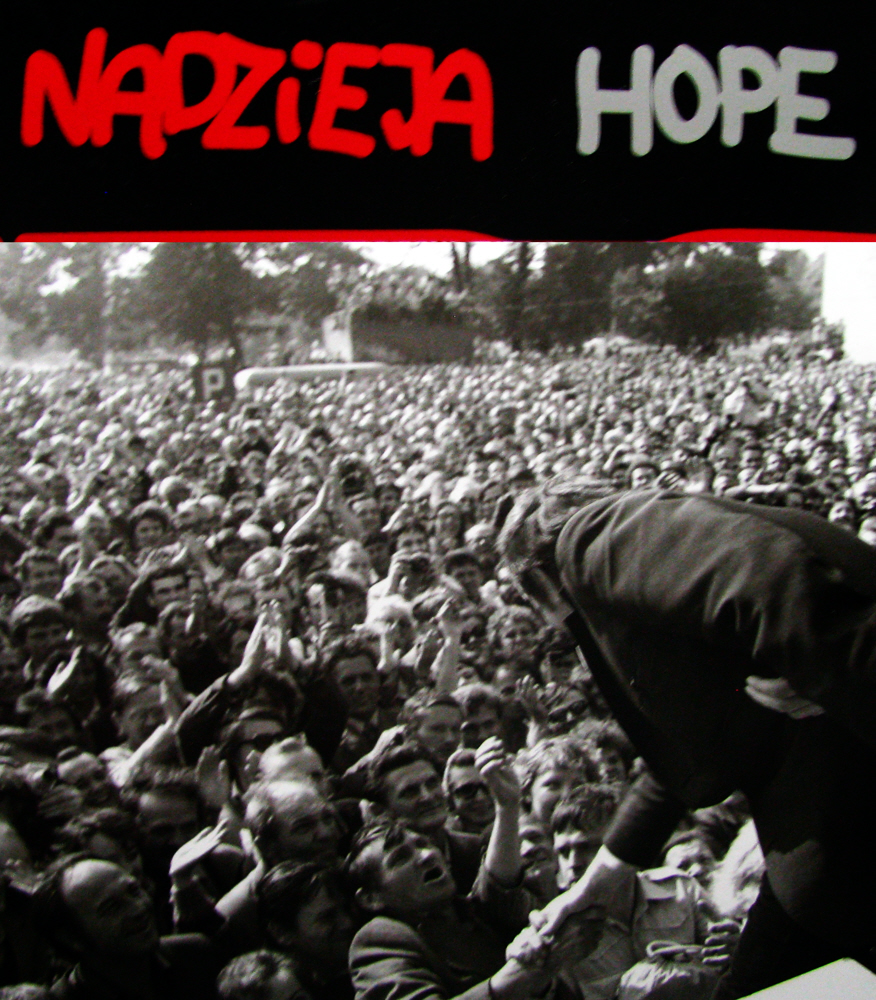

The all-pervasive euphoria on display during meeting with leaders of the strike in the Gdańsk shipyard (Panel from the Solidarity exhibit, brought to Madison in 2012 and co-sponsored by PHC-Madison)

The MKS recognized the importance of access to reliable sources of information by placing the freedom of speech, the press and publication as No. 3 on the famous list of 21 demands issued on August 17, 1980. To be clear, the Polish Constitution of 1952, then in effect, already guaranteed the freedom of speech and the press, along with other rights observed in civilized societies. Yet, the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR) ruled the country based on its own statutes – constitution was relegated to the role of a legitimacy smokescreen. The cornerstone of the PZPR rule was its strict control over information needed to subdue people into submission. Relentless censorship was the rule of the day, creating a market for the underground publishing – and in this area, Poland had strong traditions going back about 200 years.

Books and periodicals published underground were known as bibuła (literally in Polish, a blotting paper) or drugi obieg (second circulation), where first circulation meant censored publications. In terms of volume, the British Library estimates that about 3,000-4,000 independent periodicals and over 6,000 books and pamphlets were published between 1976 and 1990. The main organizers of the underground publishing before Solidarity was born included the Movement for Defense of Human and Civic Rights (ROPCiO) and Workers’ Defense Committee (KOR). It is thanks to their activities – such as helping to smuggle printing supplies from abroad or obtain them illegally from the official publishing houses – that the underground publishers of various sizes could flourish.

Entering the Solidarity era, the volume of independent publications skyrocketed, while their profile changed from the predominantly book-oriented to the one focused on periodicals and other more or less serial news publications produced in nearly every corner of Poland. Although rarely prosecuted, vast majority of them was still published illegally or semi-legally – with help of printing supplies flowing in from sympathetic trade unions in the West. Circulation varied from hundreds in smaller workplaces to 30,000 for the newsletter published in the Gdańsk shipyard during the strike.

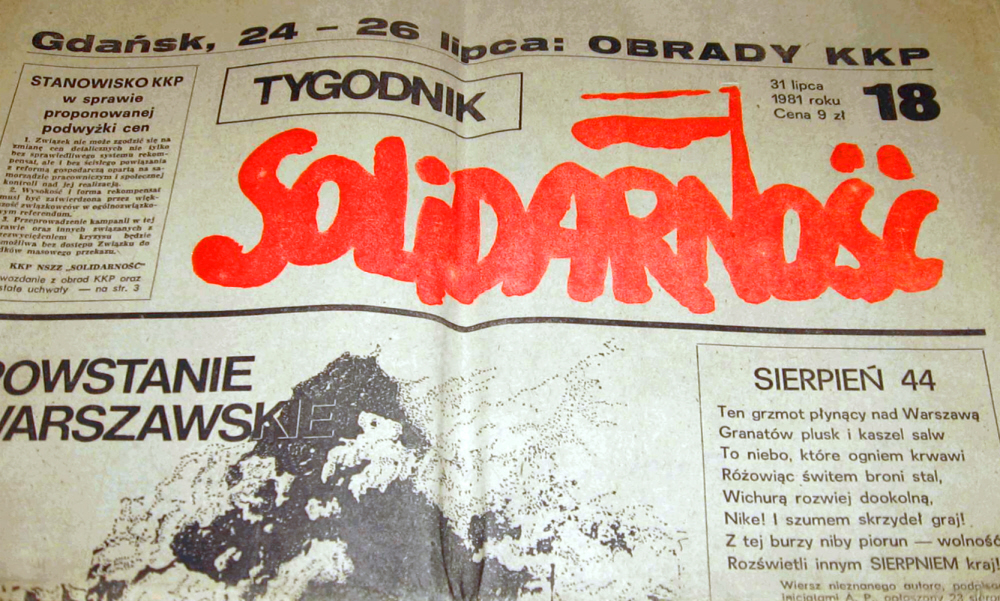

Only two periodicals received the governmental consent. The weekly Unity (Jedność) was published in Szczecin until December 1981, with circulation up to 150,000 for some special issues. On the other hand, the Solidarity Weekly (Tygodnik Solidarność, see image near the title), led by Tadeusz Mazowiecki (later the prime minister of Poland, 1989-1990), reached circulation of 500,000. These numbers could easily be higher but the governmental approval came at the price. One was that paper rationing was limiting the number of printed copies. Another price to pay was that despite a significant leeway, both magazines were still subjected to censorship.

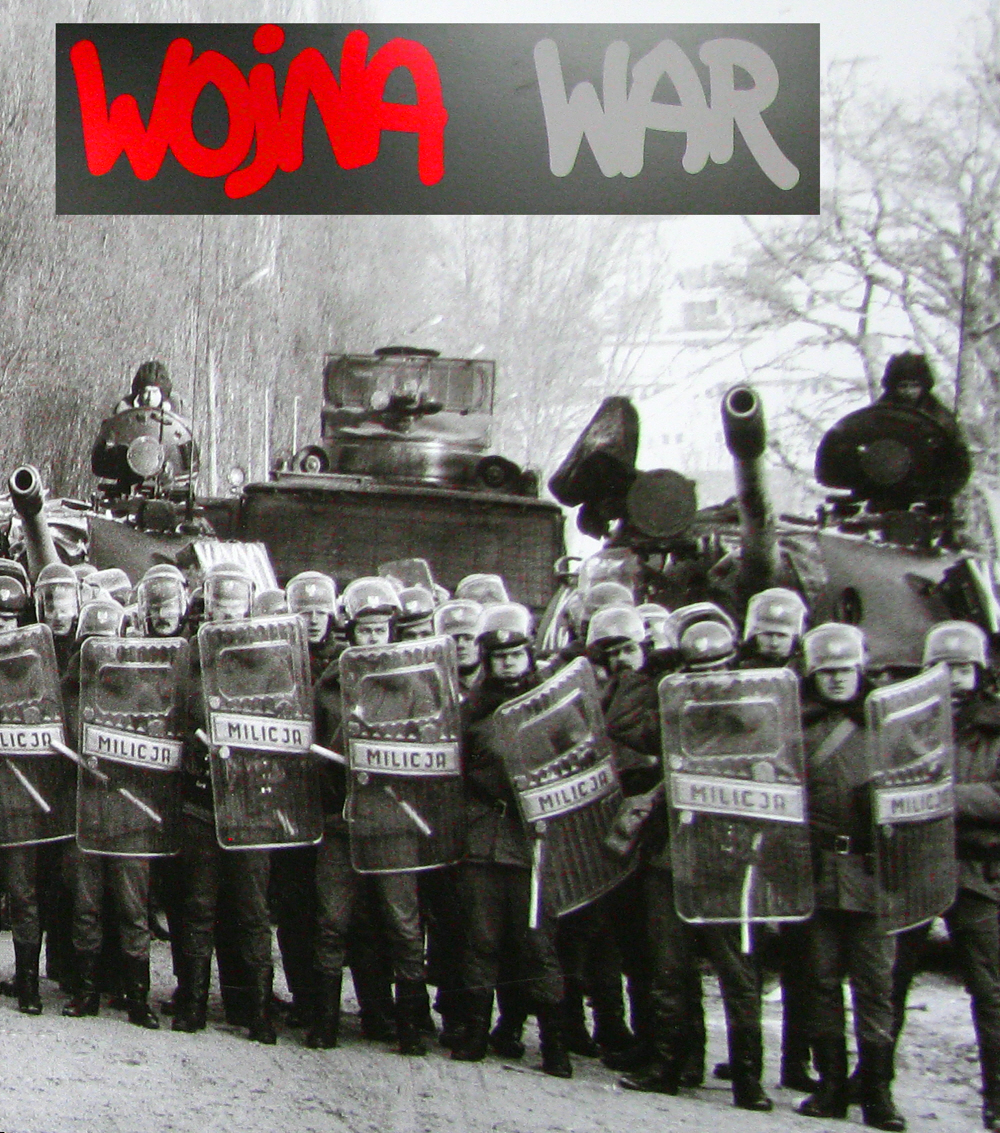

The lively publishing activities came to a screeching halt when the next first secretary, General Wojciech Jaruzelski – unable to fix the economy and prevent further disintegration of the communist system – declared the martial law on Sunday, December 13, 1981. In the pitiless crackdown on the Solidarity movement, thousands of tanks and armored combat vehicles hit the roads, along with over 100,000 soldiers and state police unleashed to squash any forms of resistance. Solidarity was stripped of its legal status. Over 10,000 people (primarily Solidarity members) ended locked up in the internments camps. The independent printing equipment was seized, radio and TV stations besieged, and telephone lines cut off under the pretext of preventing the “spread of misinformation.”

Riot troops called ZOMO (Motorized Reserve of the Citizens’ Militia) and military ready to attack the workers striking in the Gdańsk shipyard on December 16, 1981 (Panel from the Solidarity exhibit, brought to Madison in 2012 and co-sponsored by PHC-Madison)

As surprising as it may seem, the damage to the publishing base proved to not last long, and at that time my encounters with Solidarity publications became more personal. Until the Solidarity regrouped and underground publishing resumed, humble typewriters were used to patch up the information void. Thousands of anonymous volunteers – including myself – painstakingly re-typed the information bulletins in as many carbon copies as typewriters would handle.

Of course, getting caught copying, or even possessing these materials, was fraught with risk of harsh punishments. I came dangerously close to finding out what they would be when one day the house where I was doing the typing was raided and searched. Everything happened so quickly that I managed only to shove the typewriter into the nearest closet (by the way, totally empty, not even one piece of cloth to use as a cover). There was also no time to remove the paper load, the incontrovertible evidence of my “misdeed.” I was mortified when three soldiers and three policemen entered the room because the typewriter’s discovery was inevitable.

Luckily for me, the gossips circulating about some soldiers having courage to side with the people proved true. The soldier ordered to check the closet started opening its sliding door, stopped moving it as soon as he saw what’s inside, gave me a long gaze, and then simply announced: “Clear!” I will never know why he did what he did but as it turned out later, one of my in-laws was the actual reason for the ride. A lawyer for years providing his services in defense of arrested demonstrators, he went into hiding after avoiding arrest on December 13 by a sheer stroke of luck.

My second brush with danger related to the possession of illegal printed matter occurred in September 1983, just few weeks after the martial law was officially lifted on July 22, 1983 (although in one form or another it persisted for next 2-3 years). Heading for the United States, I arrived at the Okęcie Airport in Warsaw with a suitcase containing several pounds of underground publications hiding under a layer of scientific papers. The view extending from the airport’s upper gallery was scary. Down below was the main hall converted into a huge check-in area, where custom and security officers tenaciously ploughed through the piles of personal possessions removed from suitcases on the long rows of tables. Yet, I descended down with some irrational hope that somehow, I will make it through. And I did…

Today these materials are a part of the Solidarity Collection, held in the Memorial Library of the University of Wisconsin-Madison – preserving the memory of people working hard and risking their freedom for a just cause.

Irena Frączek

Reprint from the newsletter published by the Polish Heritage Club, Wisconsin Madison

Archived Posts

- 80th Anniversary of the 1944 Warsaw Uprising

- 2024 Wianki Festival

- 2024 Polish Constitution Day in Wisconsin

- 2023 Merry Christmas

- 2023 Lighting the Light of Freedom on Dec 13 at 7:30pm

- Independence Day and Veteran Day invitation

- 2023 Wianki Festival

- 2023 May 3rd Constitution Day Celebration

- 2023 Lecture on Polish Borders by Prof. Don Pienkos

- 2023 REMEMBER THIS: Jan Karski movie premieres on PBS Wisconsin

- 2023 Upcoming lectures in the Polish Center of Wisconsin

- 2022 Polish National Independence Day

- 2022 Independence and Veteran Day Luncheon (invitation)

- 2022 Wianki, Polish Celebration of Noc Świętojańska (St. John’s Night)

- Celebrating Constitution of May 3, 1791 in Polish Center of Wisconsin

- 2022 Polish Constitution Day, Polish Flag Day and the Day of Polonia

- 2022 March Bulletin

- 2022 Polonia For Ukraine Donations

- 2022 Polish American Congress Condemns Russian Invasion of Ukraine

- 2022 PAC-WI State Division Letters to WI Senators and Representatives

- 2021 Polish Christmas Carols

- 2021 Panel Discussion: Martial Law in Poland 1981-1983 (REPORT)

- 2021 Panel Discussion: Martial Law. Poland 1981-1983 (invitation)

- 2021 Solidarity: Underground Publishing and Martial Law 1981-1983

- 2021 Polish Independence Day and Veterans Day

- 2021 Polish Independence Day and Veterans Day Luncheon

- 2021 Prof. Pienkos lecture: Polish Vote in US Presidential Elections

- 2021 POLISH HERITAGE MONTH EVENTS

- 2021 “Freedom” Monument Unveiled in Stevens Point, Wisconsin

- 2021 PCW Picnic and Fair

- 2021 Remembering Września Children Strikes (1901-1903)

- 2021 May 3 Constitution Day

- 2021 DYKP Contest Winners and Answers

- 2021 DYKP CONTEST EXTENDED and CASIMIR PULASKI DAY

- 2021 February announcements

- 2021 Polish Ministry of Education and Science oficials visit Wisconsin

- 2021 DYKP Contest, KF Gallery and Dr. Pease lectures

- 2020 Help Enact Resolution commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Katyn Massacre

- 2020 Independence And Veterans Day

- 2020 Remembering Paderewski

- 2020 POLISH HERITAGE MONTH

- 2020 Solidarity born 40 years ago

- 2020 Battle of Warsaw Centenary

- 2020 The Warsaw Rising Remembrance

- 2020 June/July News: Polish Elections, Polish Films Online and more

- 2020 Poland: Virtual Tours

- Centennial of John Paul II’s Birth

- 2020 Celebrating Polish Flag, Polonia and Constitution of May 3rd

- 2020 Polish Easter Traditions

- 2020 Census and Annual Election

- Flavor of Poland (Update 3)

- 2020 Copernicus, Banach & Enigma talk

- 2020 Do You Know Poland and other announcements

- 2020 Flavor of Poland (Update 2)

- 2020 People and Events of the Year

- 2019 Holidays

- 2019 December Medley

- 2019 Independence Celebration

- 2019 Independence Invitation