2018 Kashube Lecture Notes

Polish/Kashube Emigration

and Immigration to Milwaukee

“One Story with Three Strains”

Speakers during the lecture that took place on September 6, 2018 included:

Prof. Anne Gurnack, Professor Emerita (Political Science), University of Wisconsin Parkside;

Abbé George Baird, Administrator St. Stanislaus Church of Milwaukee;

Sebastian Tyrakowski, Deputy Director of the Emigration Museum in Gdynia Poland.

Moderator: Dr. Angela Pienkos, Educator, Past President of the Polish American Historical Association and Past Executive Director of the Polish Center of Wisconsin.

LECTURE NOTES

by David Rydzewski

The Kashubian people are a Polish ethnic group with its own language, customs and traditions. Since 2005, the distinctive dialect they speak is officially recognized as the regional language.

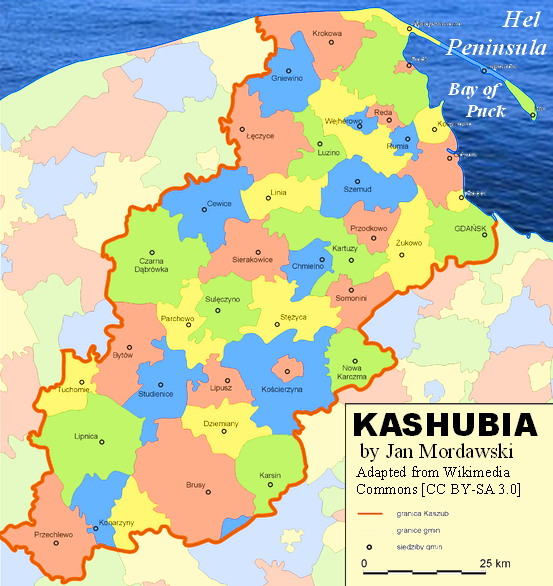

The Kashubes that settled on Milwaukee’s Jones Island, came from the Hel Peninsula area of Poland. The Hel Peninsula is a long narrow strip of land that separates the Bay of Puck from the open Baltic Sea, They came to the area of Milwaukee that allowed them to do what they knew best,  fishing. The Kashube emigration started in the 1870’s. Many of the first Kashube emigrants originated in southern Kashubia (furthest away from the Baltic coast) and settled in Canada. They later found the land in Canada not well suited for farming, and many of them resettled in Stevens Point, Wisconsin or Winona, Minnesota.

fishing. The Kashube emigration started in the 1870’s. Many of the first Kashube emigrants originated in southern Kashubia (furthest away from the Baltic coast) and settled in Canada. They later found the land in Canada not well suited for farming, and many of them resettled in Stevens Point, Wisconsin or Winona, Minnesota.

The Kashubes from the Hel Peninsula came a little later and settled on Milwaukee’s Jones Island. Jones Island was then a relatively small place outside of Milwaukee proper, so it had few or no city services. But to the Kashubes it was their new home. The first child born on the island was named Felix Struck, and curiously he was the last person to live on Jones Island, before the city of Milwaukee bought all of the land on the island for its water treatment plant and harbor docks.

By the 1890’s Jones Island was a thriving fishing village of about two thousand people. Two thirds of them were Kashubes, with Norwegians and Germans making up the rest of its population. Lacking many city services, its residents started a school on the island, with teachers making the trek each day from shore to the school that went up to the third grade.

When Jones Island was first being settled, properties were built, sometimes without clear title to land. For a while that worked, but later land claims were contested between islanders and the Illinois Steel Company. Over 80 lawsuits went to trial, trying to determine lawful owners. Islanders found mixed results in those court decisions. Today there is a small park on Jones Island that commemorates the Kashube settlers, and each August, many Kashube descendants of those early settlers come together for a picnic.

St. Stanislaus Bishop and Martyr Church was built in 1866. It was Wisconsin’s first urban Polish Church, and it became the center of the Jones Island Kashube’s religious and cultural life. Enormous financial sacrifices were made by the Kashubes in support of the church. Today the names of those some of those Kashube pioneers can be found cast into the four brass bells in the St. Stan’s steeples. Those names include Kanski, Palmbeck, Flander, Konkel, and many more.

Today St. Stan’s is considered by many to be the mother church for other area Polish parishes. In 2016, St Stan’s celebrated its 150th anniversary. Abbé George Baird, serving at St. Stans, told of its growing faith community and its major restoration’s efforts. A video and photos that were shown testify to the successful efforts made to renew this beautiful church. St. Stanislaus Bishop and Martyr church is one of the few parishes in the Milwaukee archdiocese that holds masses in Latin.

Details of the work at the Emigration Museum in Gdynia, Poland were given by its Deputy Director Sebastian Tyrakowski (accompanied by Dr. Rafał Kaczyński, Research Officer). The Emigration Museum of Gdynia was opened in 2015. It tells the story of the emigration of three and a half million Polish people to new lives in foreign lands.

The site of the museum in Gdynia is what had once been a 1933 built terminal for ocean liners. Destroyed during the Second World War, its rebuild started in 2012. To help frame the strong emotion that attaches to this center of Polish emigration, the building is filled with Polish patriotic symbols.

The first major push for Polish emigration started after the failed November Uprising (1830-1831) that began with the Cadet’s Revolt of 1830. The museum tells the story of this uprising and the resulting migration of people from rural areas to cities and abroad. To help personalize these events, one family’s experience is told in detail. The trauma a family goes through in leaving its home, family and traditional way of life behind is portrayed. One of those stories covers a family leaving its cottage in Galicia, embarking on a crowded ship to New York’s Ellis Island, and later moving on to Chicago.

Causes of this emigration, from the personal, political, economic, and threat of war, are told. Included is the story of “Brazilian Fever,” where tens of thousands of Poles left for Brazil, in search of free land and opportunities, only to discover jungle, tropical diseases, and a world they did not expect. Many of those who tried Brazil, later went on to the U.S. and Canada.

The Museum contains core and temporary exhibits. It also serves as home for cultural, educational and historic projects, and provides a venue for musical events, plays, lectures, conferences, and workshops. Finally, it hosts a section on oral history and publishes its own scientific journal. Emigration Museum of Gdynia, stands as a lasting link and symbol of Poland’s connection to World Polonia.

Archived Posts

- 80th Anniversary of the 1944 Warsaw Uprising

- 2024 Wianki Festival

- 2024 Polish Constitution Day in Wisconsin

- 2023 Merry Christmas

- 2023 Lighting the Light of Freedom on Dec 13 at 7:30pm

- Independence Day and Veteran Day invitation

- 2023 Wianki Festival

- 2023 May 3rd Constitution Day Celebration

- 2023 Lecture on Polish Borders by Prof. Don Pienkos

- 2023 REMEMBER THIS: Jan Karski movie premieres on PBS Wisconsin

- 2023 Upcoming lectures in the Polish Center of Wisconsin

- 2022 Polish National Independence Day

- 2022 Independence and Veteran Day Luncheon (invitation)

- 2022 Wianki, Polish Celebration of Noc Świętojańska (St. John’s Night)

- Celebrating Constitution of May 3, 1791 in Polish Center of Wisconsin

- 2022 Polish Constitution Day, Polish Flag Day and the Day of Polonia

- 2022 March Bulletin

- 2022 Polonia For Ukraine Donations

- 2022 Polish American Congress Condemns Russian Invasion of Ukraine

- 2022 PAC-WI State Division Letters to WI Senators and Representatives

- 2021 Polish Christmas Carols

- 2021 Panel Discussion: Martial Law in Poland 1981-1983 (REPORT)

- 2021 Panel Discussion: Martial Law. Poland 1981-1983 (invitation)

- 2021 Solidarity: Underground Publishing and Martial Law 1981-1983

- 2021 Polish Independence Day and Veterans Day

- 2021 Polish Independence Day and Veterans Day Luncheon

- 2021 Prof. Pienkos lecture: Polish Vote in US Presidential Elections

- 2021 POLISH HERITAGE MONTH EVENTS

- 2021 “Freedom” Monument Unveiled in Stevens Point, Wisconsin

- 2021 PCW Picnic and Fair

- 2021 Remembering Września Children Strikes (1901-1903)

- 2021 May 3 Constitution Day

- 2021 DYKP Contest Winners and Answers

- 2021 DYKP CONTEST EXTENDED and CASIMIR PULASKI DAY

- 2021 February announcements

- 2021 Polish Ministry of Education and Science oficials visit Wisconsin

- 2021 DYKP Contest, KF Gallery and Dr. Pease lectures

- 2020 Help Enact Resolution commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Katyn Massacre

- 2020 Independence And Veterans Day

- 2020 Remembering Paderewski

- 2020 POLISH HERITAGE MONTH

- 2020 Solidarity born 40 years ago

- 2020 Battle of Warsaw Centenary

- 2020 The Warsaw Rising Remembrance

- 2020 June/July News: Polish Elections, Polish Films Online and more

- 2020 Poland: Virtual Tours

- Centennial of John Paul II’s Birth

- 2020 Celebrating Polish Flag, Polonia and Constitution of May 3rd

- 2020 Polish Easter Traditions

- 2020 Census and Annual Election

- Flavor of Poland (Update 3)

- 2020 Copernicus, Banach & Enigma talk

- 2020 Do You Know Poland and other announcements

- 2020 Flavor of Poland (Update 2)

- 2020 People and Events of the Year

- 2019 Holidays

- 2019 December Medley

- 2019 Independence Celebration

- 2019 Independence Invitation